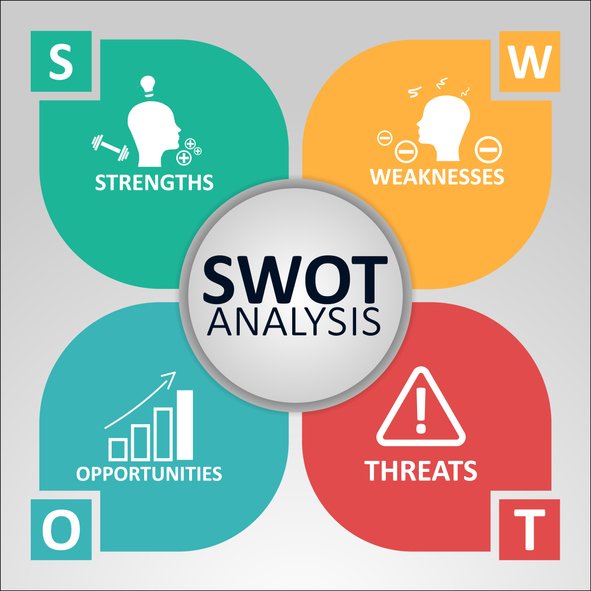

Strategic Planning SWOT

At Intertech, we’ve just completed our annual planning to set our strategies, goals, and projects for the coming year. All planning participants complete an exhaustive survey in advance. Employees not participating in the retreat take part in a half-day working session we call a town hall. They share ideas and provide feedback in a confidential format. We use all this information in a SWOT analysis, which is reviewed, analyzed, and defines next year’s plan. Here’s the SWOT template we use at our retreat.