In the post on my friend Pete Remembering What Matters, One Step at a Time, (thanks again to those of you who supported him by donating via his blog), I mentioned my dad. It reminded of an article I wrote about him titled “Lessons from My Father.”

In the post on my friend Pete Remembering What Matters, One Step at a Time, (thanks again to those of you who supported him by donating via his blog), I mentioned my dad. It reminded of an article I wrote about him titled “Lessons from My Father.”

It was printed the first Father’s Day after his death and was published in Octane, The Entrepreneur’s Organization Magazine. Below is a copy.

Lessons from My Father

For many, Father’s Day is a holiday of the worst possible definition: a phony event designed to sell cards and neck ties.

For me, though, this Father’s Day has special poignancy: It’s the first time I’ll be celebrating as a dad myself, and the first time that I won’t be able to tell my own dad how much he means to me.

My father, Theodore, died last year in a farming accident. It was a terrible shock, to say the least, and it put my life in perspective. In the months since, I find myself remembering all the things he taught me; lessons that I want to teach Theodore, my young son.

In 2001, a local newspaper published an article about how my company, Intertech, was named one of the 500 fastest growing firms in the nation. In the article, I credited some of my success to simple lessons that my dad taught me. Now I realize that my dad taught me so much more, and those lessons have been critical to my company’s ongoing success.

“Tell the truth and you’ll only have one story to remember” was one of his favorite sayings. After being in business for 20 years, I have repeatedly experienced the merit of my dad’s wisdom. Recently, an important client of ours hired a CIO who turned out to be a dishonest bully. He hoped posturing, changing his story and saying whatever would resonate with me would make me complicit with his deceit. It didn’t. The company fired him, but Intertech is still engaged.

This particular experience taught me that while it’s easy to encourage others to tell the truth, it’s harder to create an environment where truth-telling feels safe. To create an atmosphere of honesty, I’ve learned to support people when they fail. I also encourage my managers to tell those people who make mistakes that they’re OK. I’ll never forget how grateful I was when my dad did that for me.

“If you do nothing, you won’t make any mistakes” were his first words after I accidently sheared the axle on his truck when I was a teenager. After reminding me that only those who do nothing are perfect, he said, “Now let’s go take a look at the truck.” No shaming reprimand; just a straightforward focus on solutions. When mistakes happen in my business, I acknowledge it, learn from it and move on to the next step. At the end of the day, the mistakes are what make us great.

“If someone does something you don’t agree with, tell him directly” was another belief my dad modeled. He wasn’t confrontational, but he did speak his mind if he disagreed or had something corrective to say. When I asked him if this was hard to do, he would just shrug his shoulders and say, “I’m not trying to win a popularity contest.” I was able to apply this lesson when a valued business partner of mine messed up. We talked through the issue and he realized that, while I recognized his mistake, I was more concerned about the future of our company and his role in helping us move forward. I’m happy to say that he’s still with us today.

While popularity wasn’t his goal, my dad was beloved by many. At his funeral, many people recalled stories of how he turned their lives around or did good work. It made me realize that sharing sincere praise is precious. This is something I have institutionalized within my company with a program that encourages employees to nominate each other for demonstrating our company values. Sometimes as leaders we get so busy that we don’t give people the acknowledgement they need to excel. At the end of the day, awareness begets success.

My dad was a modest farmer, but he left a rich legacy of integrity, authenticity and kindness. His wisdom has helped me grow as a business owner and father. I only hope I can be at least half as effective in passing that legacy on to his namesake.

A digital copy of the printed magazine with this article is available at: http://www.intertech.com/downloads/pr/eo-octane-june-2011.pdf

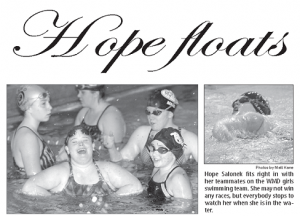

The Herald Journal printed a wonderful, inspirational article on my niece Hope.

The Herald Journal printed a wonderful, inspirational article on my niece Hope.