Top 15 Worst Computer Software Blunders

These Top 15 Worst Computer Software Blunders led to embarrassment, massive financial losses, and even death.

These Top 15 Worst Computer Software Blunders led to embarrassment, massive financial losses, and even death.

These Top 15 Worst Computer Software Blunders led to embarrassment, massive financial losses, and even death.

These Top 15 Worst Computer Software Blunders led to embarrassment, massive financial losses, and even death.

For the ninth time, Intertech was named one of the Best Places to Work by the Minneapolis St. Paul Business Journal.

For the ninth time, Intertech was named one of the Best Places to Work by the Minneapolis St. Paul Business Journal.

My thanks to our employees and customers for making us possible.

As one of The Business Journal’s Fast 50 (the Fast 50 are the fastest-growing private companies in the Twin Cities, based on revenue growth over the past three years), I was interviewed on the impact of my dad on the business. If you’re a subscriber to the Business Journal, you can access Why Dad remains top mentor choice online. If not, the brief interview is below.

As one of The Business Journal’s Fast 50 (the Fast 50 are the fastest-growing private companies in the Twin Cities, based on revenue growth over the past three years), I was interviewed on the impact of my dad on the business. If you’re a subscriber to the Business Journal, you can access Why Dad remains top mentor choice online. If not, the brief interview is below.

—

Intertech Inc.

Headquarters: Eagan

Business: IT training and consulting services

Answering: Tom Salonek, CEO

Dad: Theodore Salonek, farmer

What is your father’s best business advice?

Tell the truth and you’ll only have one story to remember.

How has your father inspired you?

“If you do nothing, you won’t make any mistakes,” were his first words to me as a teenager after learning that I accidently had sheared the axel on his truck. There was no shaming reprimand, just a straightforward focus on solutions. What a great lesson for anyone who manages fallible human beings!

How has your dad supported you?

He was encouraging and quick to tell me he was proud of what I and the firm had become.

—

While CEOs of publicly held companies ultimately are responsible to a board of directors, those of us running private companies do not share this mandate. A recent article in the April issue of Harvard Business Review, “What CEOs Really Think of Their Boards” by Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, Melanie Kusin and Elise Walton, reinforced the importance of soliciting a board’s perspective even for privately held companies such as Intertech.

While CEOs of publicly held companies ultimately are responsible to a board of directors, those of us running private companies do not share this mandate. A recent article in the April issue of Harvard Business Review, “What CEOs Really Think of Their Boards” by Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, Melanie Kusin and Elise Walton, reinforced the importance of soliciting a board’s perspective even for privately held companies such as Intertech.

The authors asked dozens of well-regarded CEOs the following questions: “What keeps boards from being as effective as they could be? Are they really the cartooned millstone around the CEO’s neck, or do they help shape the enterprise in positive ways? What can boards do to become a greater strategic asset?”

The answers are distilled into five recommendations:

Ok, current and future board members, you have your marching orders!

But what should a CEO keep in mind when working with a board? And how can private companies benefit from the wisdom of an experienced board? In my next few posts I’ll explore this topic and share best practices from my past decade of work with Intertech’s stellar board of advisors.

What do wineries, 911 call centers, and South Korea’s largest cell phone carrier have in common? Intertech’s team has built mobile applications for all of them.

In this final post in the series For Mobile Devices, Think Apps (not ads!), I’m sharing a few examples of what we’ve built for our customers.

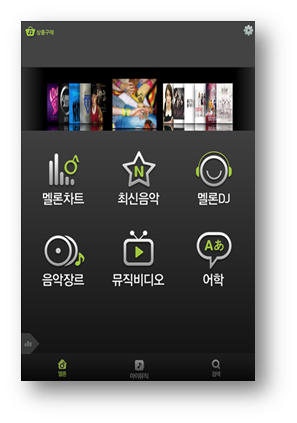

A Media App for a Mobile Phone Carrier

Working the largest mobile phone company in South Korea, Intertech developed an interface for a service similar to iTunes or Spotify.

911 Call Centers

Intertech created a mobile application for 911 call centers for the reservation of channels on radio networks. Part of the solution was a “quick schedule” to reserve a channel immediately with one touch.

Multiple Mobiles for a Health Insurance Company

For an existing customer’s application, Intertech extended their platform with a mobile version of an application’s admin, client, and public portals.

Adding Attaboys to Facebook

Have you ever sent an “attaboy” (name changed to protect the client) on Facebook? If you have, you were using an application created by Intertech. This app integrates Facebook accounts allowing posting a thanks to someone’s wall or timeline.

Mobile, One Vine at a Time

If there ever was a project where we should have taken “in kind” payment…this was it! Built for iPads and iPhones, this Intertech created application helps vineyards manage field production.

If we could be of help on a mobile project or help your team spin-up on mobile app development, please let me know.